“We can and must always make ‘Asia’ and ‘Asian American’ signify more than American exceptionalism.”

—Yen Le Espiritu, Lisa Lowe, and Lisa Yoneyama, “Transpacific Entanglements”

I begin with this quote in order to center transnational activism and to introduce the conversation that I’ll be having with activist Jungmin Choi, which is a continuation of a previous conversation. I met Jungmin through my brother, the journalist Joseph Kim. Jungmin has been an activist and organizer for over a decade. Affiliated with the transnational anti-war organization World Without War, she has worked against the international arms trade and the exportation of Korean-made police weapons, such as tear-gas and water cannons. Akin to the work that Lisa Lowe, Lisa Yoneyama, and Yen Le Espiritu offers us in terms of transnational theoretical reach and scope, Jungmin’s activism works to create effective tools against empire, by researching and intervening into the material production of war, in pursuit of a world without.

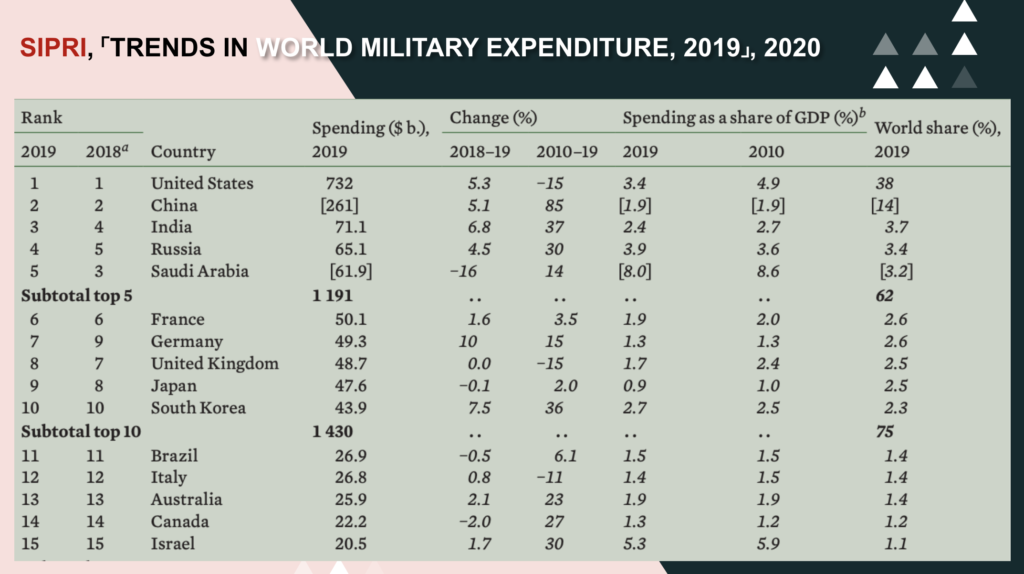

Through our correspondence and in learning more about progressive activism in Korea, I learned that Korea is ranked 10th amongst global weapons importers and exporters, and the country buys mostly from the United States. I remain struck by how Jungmin and her colleagues work towards networks of transnational solidarity, in which nationalistic politics are forgone in pursuit of global liberation.

Eunsong: I was wondering if we could begin by discussing this video in order to grapple with the interconnections between Korea, the US, and the industry of war, and your efforts to make explicit their relationships. It’s hard to imagine that this weapons expo occurred fall of 2020, amidst a global and ongoing pandemic. Various weapons manufacturers from across the globe congregated in Korea to sell and buy more weapons. It is as if nothing will stop them—until we stop them. Could you speak to us about your efforts to disrupt this expo, and how your approach to protesting has been altered through the pandemic?

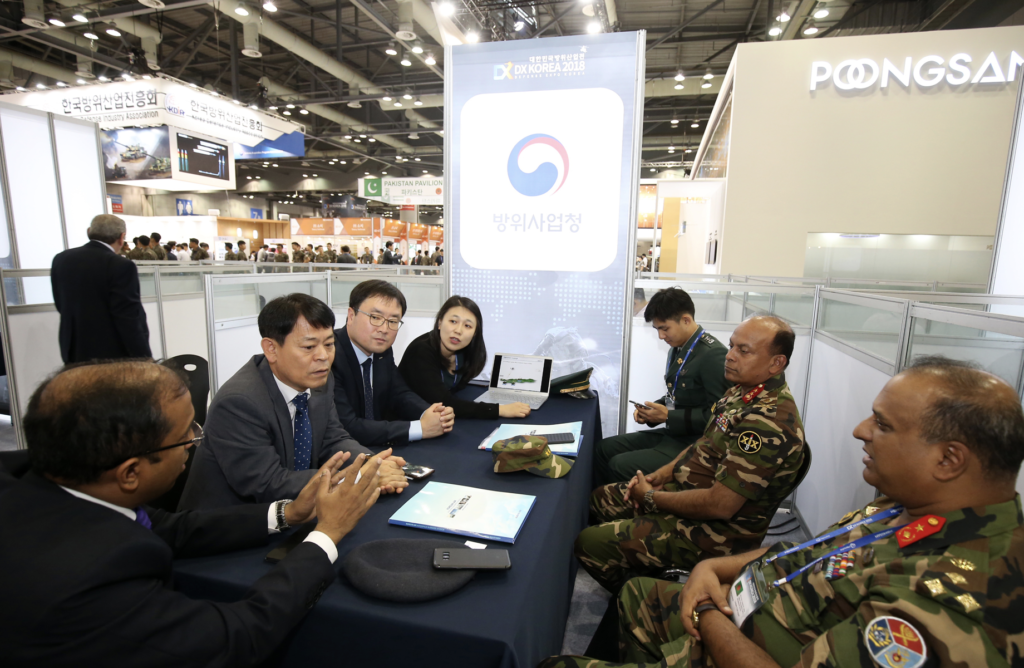

Jungmin: Yes, that’s right. They won’t stop unless we stop them. Even COVID-19 couldn’t stop them. They just postponed what they were supposed to do in September for two months. DX KOREA 2020 is the first defense industry exhibition to be held in Asia last year. And ADEX will happen in 2021. The majority of the world’s defense industry exhibitions were cancelled or postponed because of COVID-19. How proud. These are the DX KOREA 2020 photos.

South Korea currently mandates two-weeks of self-isolation for incoming travelers, but those traveling to South Korea to attend the exhibition were exempted from these health measures. Though the organizers said that safety and prevention were their top priorities, senior Pakistani, Kazakhstan, and Nigerian military personnel tested positive for COVID-19 and had to be quarantined. Currently, the South Korean government is internationally known for successfully containing and preventing the spread of COVID-19, and their measures include self-isolation for incoming visitors and limiting large gatherings. These rules were not applied to those attending DX Korea 2020, again: exceptions were made and granted for arms dealers. Though criminal penalties have been enacted against travelers who break the strict self-isolation measures, overseas arms dealers were exempt from quarantining. This contradiction is difficult to justify. The international sale of weapons is prioritized over the safety of the world.

The pandemic has not only impacted World Without War but social movements across the globe. Some might say that movements have shrunk in size as gathering in person is not easy. However and hopefully, I believe that creative forms of protests have been developed in spite of the restrictions, particularly via online activities.

For example, the Seoul Queer Parade this year allowed people to choose a hairstyle, outfit, and picket, and participate in the online pride march.

There was also an online exhibition. Because we couldn’t hold an offline event, a VR exhibition and video commentary were imagined as its substitute.

Offline protests were very limited. Because meeting in person while respecting quarantine guidelines became difficult. Thus when we did physically meet we coordinated how to safely meet in advance. Participants wore masks and gloves, we checked each other’s temperatures and distanced. We were able to demonstrate because we took these measures.

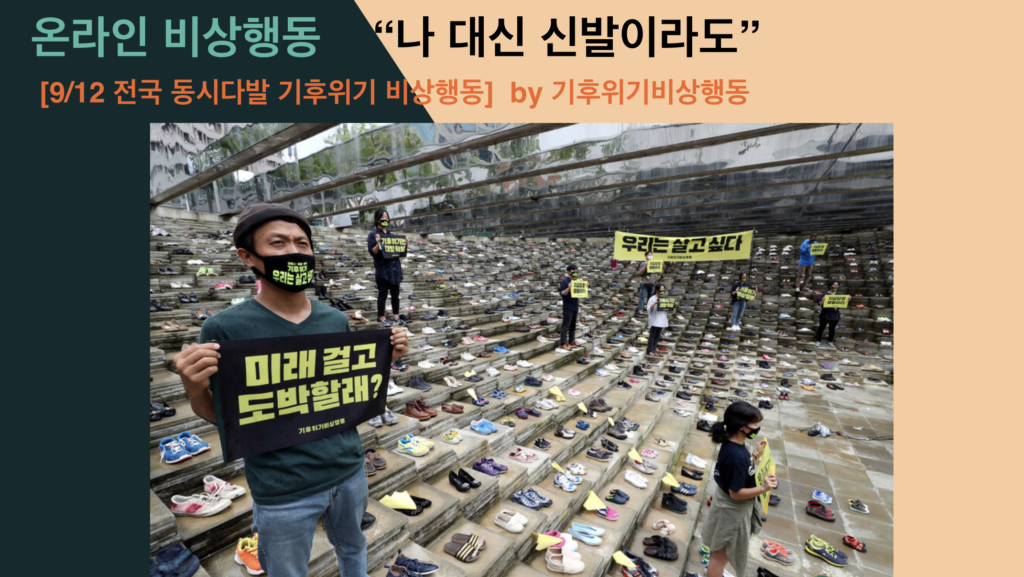

In the meantime, there were many interesting and creative protest ideas. In order to limit exposure to COVID-19, there was a rally where an avatar was set up instead of people, a demonstration where shoes were set up on behalf of protestors, and a parade with cars. In Seoul, demonstrating in your car has not been a common form of protest. The city is dense and the public transportation infrastructure is complex. Anyway, during the pandemic, there were various attempts to reveal social injustice, and I introduced them because I think we need to learn from each other and organize better actions.

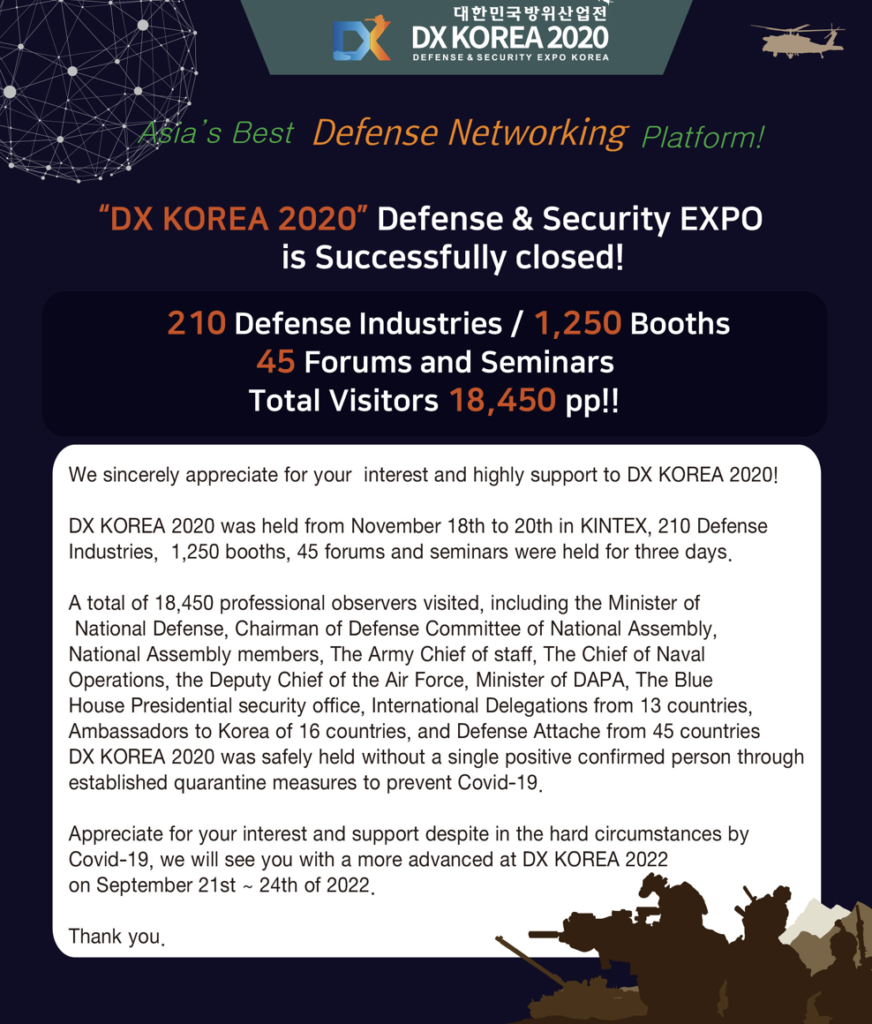

This is a thank you message posted on the website of DX KOREA 2020 after the expo. It is a lie that there was no positive confirmed person in the message. Anyway, they say they are going to see us again in 2022, so we will definitely visit them.

South Korea is not only hosting DX Korea, there are other arms shows on the way. ADEX, is an air force expo that ranks in the top 30 of the world arms fairs, and there is Korea Police World Expo, which is the only security industry fair in East Asia that was started two years ago. As such, in modern society, the arms fair is functioning as a market to display and buy and sell “cutting-edge” weapons.

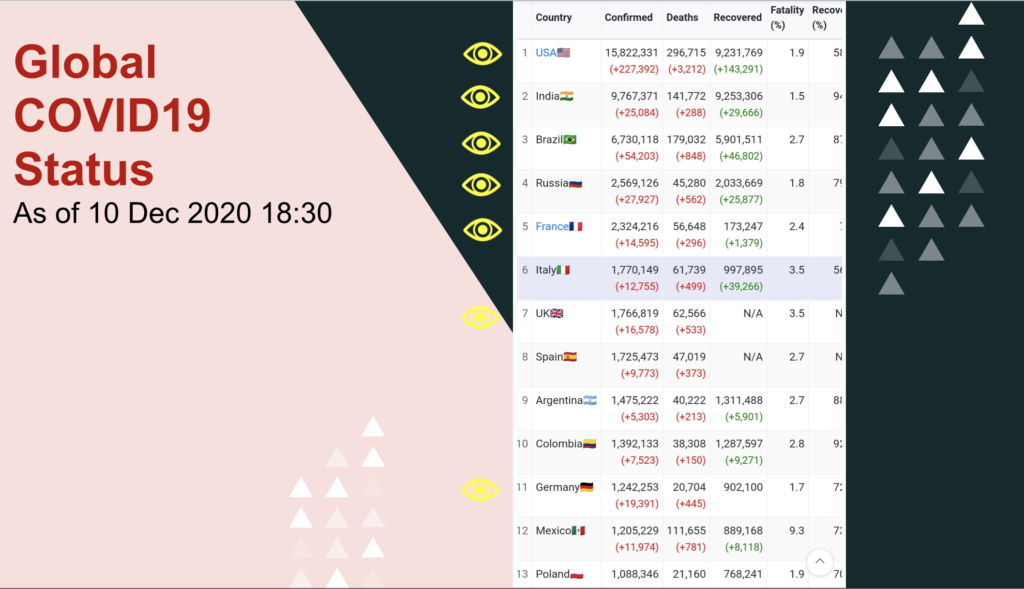

Finally, please look at the global military spending in 2019. Take a good look at the list of countries that appeared here. And now this is the current status of COVID-19 around the world as of December 10th. Can you see the names of familiar countries? These are the world’s largest military spending countries you’ve seen earlier. It’s time for the whole world to think about what security means and what really guarantees our safety.

It’s time for the whole world to think about what security means and what really guarantees our safety.

Eunsong: Thank you so much. Something that I’m hoping we could highlight are the efforts required of transnational activism, which supersede national borders. I think something people from non-colonized (or not recently colonized) histories might not understand is how the categories of “conservative” and “liberal” shift through the experience of colonization. Activists and radical historians have helped me understand that in Korea, conservative often denotes those who want and seek US & western (colonial) protectionism. You see them holding US flags and speaking with admiration about the US and against Koreans who reject US military occupation and influence. Thus, those who oppose them—the liberals—in Korea is a mixture of some anti-US sentiment which is really in service to strengthen Korean nationalism. Either way, the US is the monster, and politics are divided between those who accept its oppression (conservative) or reject it for statehood (liberal). Which brings me to ask: what is progressive and radical, in this landscape? Your activism rejects both projects—nationalism and US subservience—and seeks to uplift those opposed by the Korean nation-state within the borders of Korea AND by those opposed by those outside the borders of the Korean nation-state. This is exemplified through your activism (beginning in 2013) against the exportation of Korean tear gas, and currently against the exportation of water cannons to Thailand. Both are weapons used against protestors. Could you talk about the experiences that lead you towards transnational liberation?

Jungmin: Honestly, it’s difficult to hear from third perspectives in South Korea. In a society where the “all or nothing” discourse prevails, those who advocate for a third way, no matter how careful and complex, become perceived as part of the “all or nothing” spectrum.

I don’t think I need to say anything more or explain why conservative Koreans wave a star bangled banner with the South Korean flag at their rallies. Of course, there might be a need for in-depth research into how alienation, poverty, racial discrimination intersect with aging populations in South Korea.

Left nationalism is a bit more complicated. This is possibly because the victims are Korean but the perpetrators were neither exclusively made in the US and Japan. However, the reality is that South Korea is the world’s 13th largest GDP and the 32nd largest economy in terms of per capita. And within this, there are about 400,000 foreign workers in the Korean economy that are being severely exploited and marginalized. Also in places like Vietnam, South Korean companies are exploiting 300,000 labourers who take low pay and work long hours. If we deny this reality and only emphasize and tend to our victimization, the harm we perpetuate becomes all the more evasive. Thus, in such a context, whether or not South Korea exports tear gas, water cannons, or other weapons becomes a problem to be resolved later. My friends and I believe that rupturing from this static nationalism and moving towards horizontal forms of civil solidarity must be prioritized, and this has never been more important for us. The campaign you speak of, of our efforts to halt the exportation of South Korean tear gas and water cannons, spring from these efforts. We spoke about what we did then in our last interview.

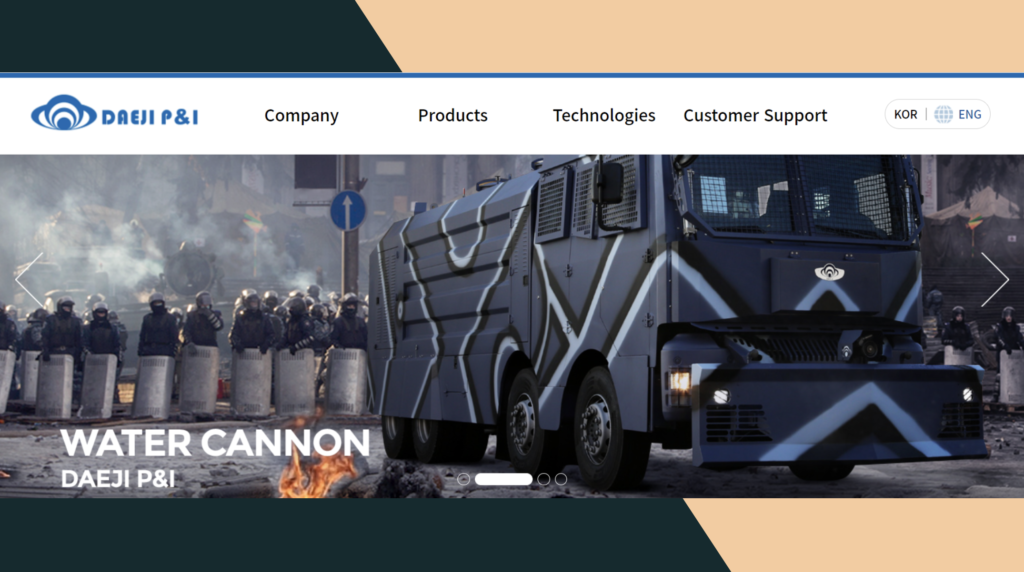

Also, World Without War has launched a campaign to stop exporting water cannons to Thailand and Indonesia from this year. Lastly, I’d like to mention the names of the water cannon producers. Daeji P&I is a company that produces water cannons and armored vehicles that have been exported to Indonesia, and these weapons have been used in West Papua against those in the independence movement fighting the colonial occupation of Indonesia. And it is JINO Motors that exports water cannons to Thailand.

Eunsong: Wow. Thank you so much. As someone who lives in the US—which feels like trying to live in the tissues of a shell corporation—I’ve been endlessly inspired by your activism in Korea. When protests after George Floyd’s murder erupted, I heard from my brother that World Without War was looking into the tear gas being used against protesters, asking questions like: where are they coming from? Who is supplying this? Are they coming from Korea? And I know you were asking this because of your previous activism around Korea’s exportation of tear gas into the Middle East and Turkey to suppress their protests. I was hoping you could speak more about your process into researching Korea’s manufacturing and exportation of tear gas, and why this has become important to you. I ask this so that we might be able to discuss your methodological approaches to activism, and how your process locates how and where the Korean nation state configures in the maintenance of global neoliberal capitalism.

Jungmin: As the name of our group suggests, the people who gather here, including myself, are those who dream of a world without war and strive to make it possible. Of course, we believe anti-war movements, such as the movement against the war in Iraq, where millions of people poured into the streets are necessary, but we also think it is important to address the causes in social structures and everyday life that make war possible. That’s why we prioritize the draft system. We support conscientious objectors and inform others about the problems of the conscription system.

And after this was established, and as the organization grew and became more stabilized, we thought that it would be possible to start a second initiative, which would be to monitor the arms trade and organize against them. Currently, this work is to resist the exportation of police weapons such as tear gas and water cannons, in addition to organizing against arms exhibitions such as ADEX, DX Korea and Korea Police World Expo. As the group becomes more stable and grows, the day will come when we can organize against another component of war.

As neoliberalism intensifies, and as social inequities become interwoven, social movements opposing them have been faced with a variety of difficulties. Social movements in South Korea face a number of social inequities that cannot be resolved by simply changing the regime, and some of the growing dissatisfaction is being absorbed into right-wing fascist groups, rather than sparking radical social transformation.

Before I go into our activities I want to point out that there are currently some Korean parallels to the emergence of far-right and Trump supporting conservative groups in the US. In South Korea, the rise is serious and linked to gender issues, particularly misogyny. In 2019, a Korean progressive magazine called Sisa-in conducted an in-depth poll titled, “Men in their 20s, who are they?” The results of the survey were dire. When it comes to discrimination against women in Korean society, 60.8% of men in their 20s answered “It’s not serious.” The average response of men over the age of 30 was 59.7%, so there was barely a difference. However, when asked how serious is “male discrimination,” 68.7% of answered “severe” and 30.5% of them answered “very serious.” And, “male discrimination” is a very bizarre concept in Korea, which was and is a patriarchal society. There’s clearly a generational shift, as men over the age of 30 responded very differently to this question, with 60.3% stating that it was “not serious.” And, unlike older men, the idea that men are being discriminated against has resulted in harm. These young men actively perpetuate misogyny in Korean society and have a lot of political influence.

With this being said, it’s been difficult because World Without War has been involved in organizing activities related to national defense or diplomacy. This makes obtaining relevant information difficult. Whenever we ask questions they respond that the answer is classified and can’t be shared. So, a lot of the information we get is either through the help of international activists or via informal methods. I say this to emphasize the importance of transnational solidarity.

There have been times when I’ve been pessimistic about our future, too. But, then I try to remember that hope comes through and will come from activism. Our task is to think about how to best share methods and resources, in order to achieve maximum results, and how in the process we can make everyone feel happy and empowered. These two tasks are important and yet difficult to achieve goals in social movements. It is easy to fall into pessimism when our activism is unsuccessful and to believe that we shouldn’t have done anything, but this is a kind of political nihilism. Then someone like Trump will be elected.

And even if our movements were successful, it would be meaningless if victory comes at the cost of burn-out for activists. Thus World Without War, rather than setting the unachievable goal, like world peace, which might not occur during my lifetime, tries to set small goals that we can work towards within the next 10 to 20 years. We try to be creative and imaginative because, in contrast to what we are trying to destroy, we are working with limited resources. So we tried to do what we could to support the Movement for Black Lives, in the States for example, by investigating the tear-gas being used against the protesters, because we believe it’s important to know who is supplying the police their weapons.

If our movements were successful, it would be meaningless if victory comes at the cost of burn-out for activists.

I’ve spoken for a while so I think this should be it. Thank you for inviting me to speak with you, thank you for paying attention to our activities, and thank you for prompting me with good questions.

Eunsong: Thank you so much Jungmin, for existing and for all that you do.

This interview was translated from Korean to English by Jungmin and myself and first took place in November 2020.

Jungmin Choi is a campaigner and nonviolence trainer at World Without War, a South Korean organization based in Seoul that supports conscientious objectors and takes action against the arms trade. She also works at the women’s counselling center, My Sister’s Place, an organization that assists Korean and migrant women who live and work near US military bases in South Korea.