Martin Sostre was supported by a variety of different organizations, defense committees, and individuals during his nearly nine years in prison from 1967-1976. Few were as important and consistent as journalist William Worthy. Over the course of three years, Worthy wrote almost a dozen articles about Sostre, two of which—“Sostre in Solitary” (Boston Sunday Globe, 1968) and “The Anguish of Martin Sostre” (Ebony, 1970)—had profound impacts on his eventual release. “Sostre in Solitary” was widely distributed to raise funds and awareness about his case. His appeal attorney Joan Franklin even ordered 1,000 copies for distribution by the NAACP. “The Anguish of Martin Sostre” prompted the police informant who framed him to recant his testimony in a 1971 affidavit after he read the article while in a rehab program in California.

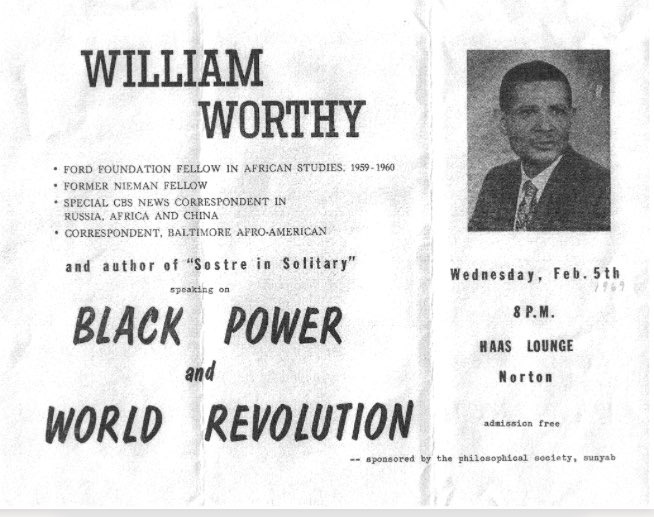

By the time the two met, Worthy was a veteran activist and journalist whose experiences traveling abroad to Communist nations had led him into similar struggles over censorship, state surveillance, political trials, and imprisonment. Just a few years older, Worthy claimed conscientious objector status during World War II and participated in the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, a direct-action campaign to test the effectiveness of the recent Supreme Court ruling, Morgan v. Virginia, which overturned racial segregation laws on interstate travel. He became a columnist for one of the largest Black newspapers in the country, the Baltimore Afro-American, and landed assignments covering the Korean War and other foreign affairs. Whether in his coverage of Black prisoners of war in North Korea and Chinese prison camps or Robert F. Williams’ exile in Cuba, Worthy’s stories represented an important counter-narrative to the parochial anticommunism of most U.S.-based journalism during the Cold War.

Worthy was targeted for his globetrotting anti-imperialist journalism. When he applied to renew his passport in 1957, it was refused by the State Department and he became, in the language of the ACLU, “a prisoner in his own country.” Worthy disregarded the decision and soon traveled to Cuba, the first of four trips he would make over the next several years. In 1960, he became one of the founding members of the Fair Play for Cuba Committee (FPCC), which was dedicated to assuring fair coverage of the new revolutionary Cuban government. While in Cuba, he also became the first to report on Robert F. Williams’ exile. But, surveilled by the State Department and the FBI, Worthy’s mail was intercepted and his plans to travel to Cuba without a passport made known. A Committee for the Freedom of William Worthy was formed, and he and his radical attorney, William Kunstler, made motions to transfer the venue of his political trial away from Miami, Florida. He was ultimately sentenced to 3 months in jail and nine months’ probation. His cases led to two landmark decisions regarding the constitutional right to travel: Worthy v. Herter (1959) and Worthy v. United States (1964). Worthy saw such attacks on travel as an extension of U.S. imperialism and political censorship: “Travel control is thought control and intellectual control.”

Worthy was also among the handful of Black radical internationalists who financially supported Martin’s campaign during the early years (which according to Sostre also included Mae Mallory, Robert F. Williams, Bobby Seale, and Jitu Weusi). Sostre eventually fired his legal team at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund in 1970 and wrote them discouraged by the lack of support he had received from Black people and organizations since his frame-up. One notable exception was William Worthy. Unfortunately, Worthy’s coverage of Sostre has gone largely unnoticed since. So too has his broader contribution to Black radical internationalism through his activism and journalism. The Martin Sostre Institute has compiled more than a half-dozen of Worthy’s articles on Sostre here to make both more widely available and known.

Citations:

William Worthy, “Martin Sostre Can’t See Lawyer, Reporter in Jail” Afro-American, August 10, 1968.

_____________, Muslim Who Broke Ban on Services for His Faith in Pen Jailed Again,” Afro-American, July 6, 1968.

_____________, “Sostre Case Witness May Face a Rocky Road,” Afro-American, May 1, 1971.

_____________, “Sostre in Solitary,” Boston Sunday Globe, September 8, 1968.

_____________, “Sostre Trial Witnesses Recants Drug Testimony,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1971.

_____________, “The Anguish of Martin Sostre,” Ebony, October 1970, 122-124, 126, 128-129, 132.

_____________, “The Truth Will Out – Even in Conservative Buffalo,” Afro-American, August 24, 1968.

H. Timothy Lovelace, Jr., “William Worthy’s Passport: Travel Restrictions and the Cold War Struggle for Civil and Human Rights,” Journal of American History, 103, 1: 107-131.

Papers of the NAACP, Supplement to Part 23: Legal Department Case Files, 1960-1972, Series B: The Northeast, Section II: New York.

Robeson Taj Frazier, The East Is Black: Cold War China and the Black Radical Imagination (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 72-107.