Eusi Kwayana is one of those people we should seek out. You may not hear his name as often as those of other African and Caribbean revolutionaries, but his story is just as important. After learning about Kwayana, I read his 1972 book The Bauxite Strike and the Old Politics, in which he rigorously details the complications of struggle in Guyana among mine workers in what would become a nationalized bauxite industry. In that classic work, Kwayana pours over the contradictions of race, class, governance, and political representation, and notes the complications of workers’ self-activity and self-organization in ways that feel eerily relevant to the problems we encounter today. And this is why we have to seek out people like Kwayana.

What lessons could we learn from a self-described “ordinary village boy,” whose life is also thoroughly interwoven into the history of social revolution in the Caribbean? We’ll never know if we don’t read as widely as possible and look beyond the big names of history to the quieter, rank-and-file, everyday people who did not gain the same fame as others by accident or on purpose. Their truths may be more piercing at times due to their ability to avoid the pitfalls that come with popularity and notoriety. Although, sometimes, it just depends on who you’re talking to. Many in Guyana acknowledge Eusi as the honorary “Sage of Buxton,” despite his humility and ability to keep a low profile.

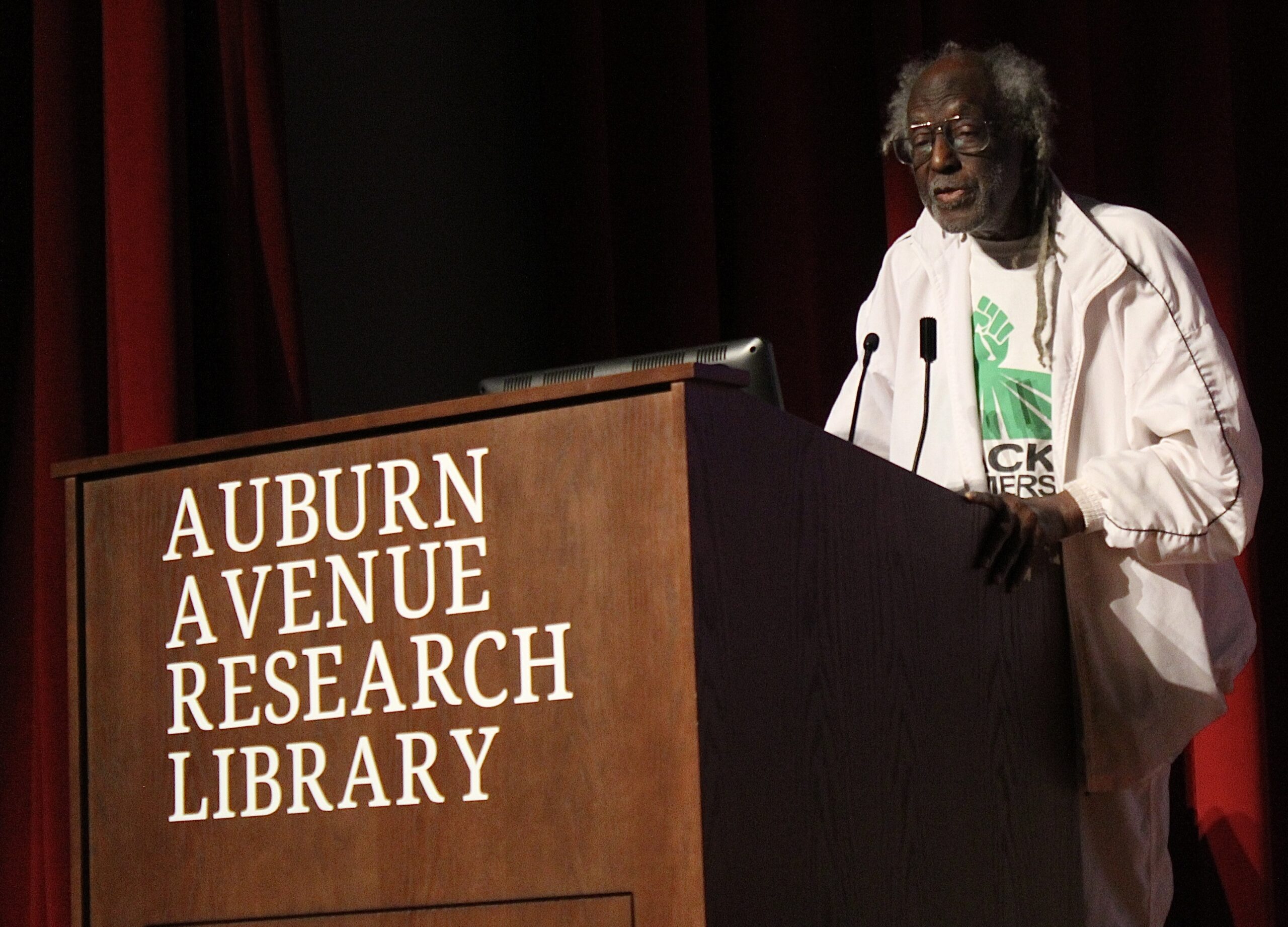

When I made contact with Eusi Kwayana on 4 November 2021, after trying to reach him for some time, his mind was one of the most stunning I’d encountered at nearly one hundred years of age. Working from only his own memory and without any notes, he recalled with ease many fascinating gems of Guyana’s revolutionary history and the radical perspectives that have animated his country over the course of his life. “The old ideologies, to me, are petering out. They were formulated in times that were different from these,” he told me as he encouraged “new thinking.”

I was struck by his choice to open up our conversation that way and I wrote it on the board above my desk. Afterward, I followed up in a subsequent conversation about this interview and asked Eusi more about the state as a vehicle for liberation based on his history in relation to the “old ideologies.” I wanted to address some of my lingering inquiries about how his positions have changed over time. The state, he said, “isn’t an appropriate instrument.” He continued by clarifying that it’s “a tool of repression” and said, “I haven’t seen it do anything else.” Maybe most importantly he told me that “people’s power is the only valid ‘state’,” and that the state question is settled through struggle “in community.” He assured me that this question is not answered by individuals. His amazing journey is underscored by much of what’s been revealed to me in these conversations.

Now, upon the rerelease of another classic work, Scars of Bondage, which he co-authored with Tchaiko Kwayana, a hugely impactful educator and pan-Africanist scholar in her own right (and wife to Eusi), we have the chance to learn more yet again. The Kwayanas’ work stands as an important heritage of radicalism in the Caribbean and throughout the Americas. Eusi may not view himself as such, but some giants tread lightly. Though they aim to not be loud about who they are and what they’ve done, their impact is too large to ever hide completely.

William C. Anderson (WCA): Hello, Brother Eusi. It’s good to talk to you. I think Modibo Kadalie may have told you that I was going to call.

Eusi Kwayana (EK): Oh yes, I spoke with him this morning. How are you?

WCA: I’m alright. I just want to tell you a little about myself. I’m a writer and author who writes about a lot of Black history and Black traditions across the spectrum of Black history, in the U.S. particularly, but I’ve been thinking about the Caribbean recently. I’ve read your books and I very much appreciate your work. If you’re okay with it, I’d like to ask you a few questions that I might publish in a journal or book at a later date. Do you have time for a few questions?

EK: Yes.

WCA: The first question I wanted to ask you is: what do you think about the current state of the world? The pandemic, the climate catastrophe, the ecological disasters that are happening, and all of these increasingly dire conditions—has any of this affected or changed your long-held feelings or politics?

EK: Well, this will take a rather extended answer.

WCA: Sure.

EK: I was thinking very much about this issue. The world has really posed some new challenges that demand a lot of new thinking from those of us who are still on the planet, especially the younger generation. My generation, we’re almost not here anymore. And the old ideologies, to me, are petering out. They were formulated in times that were different from these. Marcuse, long, long ago, pointed out that technology would overcome a lot of it, but technology has been a main factor in the climate crises. Even to the governments and powers that be in the present age, these are problems that they are not prepared to cope with. Our philosophy of government, if divisive… I can give one example from Guyana, the country I come from. It is a pet example of mine, because I think it is very significant. I hope I’m not boring you yet.

WCA: No, no, no! Please speak freely.

EK: Well, we have an attorney general [in Guyana]. He’s a young man and has his own history. I don’t know too much about him, but he won the election in 2020. One of the first things he said after winning the election, in the idiom of a well-known world scripture, was “The big tree of the PPP [People’s Progressive Party],”—that’s the ruling party in Guyana—“represents the triumph of good over evil.” That struck me—and he said it more than once. Unfortunately, no one has commented on it other than myself. He is dividing Guyana, a small country of less than one million people, into a binary sort of organism—some good, some evil—on the basis of a general election. These two things have nothing in common! If he is a philosopher looking for virtue, it is not to be found in that way: by identifying as virtuous those who voted one way and the evil as those who voted another way. So, that is the kind of conflict posed at the periphery. This is not even a major power, you know? We were very petty until oil was discovered some years ago, and now we are drunk with oil money and make all these drunk statements, but that is just a representation of what is going on elsewhere.

When you look at Europe, and Ukraine, Russia, China, and so on, all of these powers have had some kind of banner, inviting humanity to their standards. All of that is done now. None of them can stand up and say “we have persisted” in their particular line of thought. A lot of it has to do with the alienation of the masses of people from the center of things. I don’t know if anything else is possible. It would have been possible with correct practice at the right time. You can’t make it possible overnight, when things are collapsing. It has to be practice and praxis, day after day, a way of life that many of the old philosophers dreamed about. But we just go along making money, exploiting resources, melting the ice, emitting dangerous greenhouse gasses, and threatening the stability of the planet.

I come from a country, Guyana, in which people are perplexed. I haven’t lived there for some time because of many of the things we are now discussing [chuckles]. I left hoping to return, but could not return to my village because it had become a battleground. I have denounced it. So here we are.

WCA: You really jumped into exactly the conversation I was hoping to have with you, by saying that the world requires new thinking and new ideas. With all of that being said, I want to ask you about ASCRIA [the African Society for Cultural Relations with Independent Africa] and your contributions to pan-Africanism, which has been pivotal. What do you think is the legacy of that work for new generations, with regard to the new ways of thinking and new ideas we need today?

EK: This is a big story—and it was not mine alone. I was just one small part of it. There are people who spent a lot of time saying that I was the central speaker of the movement because that’s convenient for them, you know? But that’s not the reality. Things do not get moving unless the people move. There is no one person who can move anything. What I wanted to point out very early is that people sometimes speak of ASCRIA in the same breath as pan-Africanism. I have let it go for many decades. Of course, part of it is true. In 1970, we organized what we called a seminar of pan-Africanists and Black revolutionary nationalists in Georgetown, Guyana. And we organized that on two principles: 1) we put out a call—it’s in print somewhere, I don’t know if you can find it—we said “Let us turn from words of support, to deeds of support.” That was an address to Africans in the Western hemisphere to cease becoming a reserve of imperialism, which we had been over the centuries, and instead become a reserve of African liberation. In that sense, we were making a contribution to pan-African struggles.

I do not regard pan-Africanism as a separate philosophy. I have not said this before. Pan-Africanism, to me, is a program. You can be of this, that, or the other philosophy and engage in pan-African struggles. Some people prefer to deem others (and themselves) something called a “Pan-Africanist.” The moment you get into that, you get various branches and genres of pan-Africanism and then all these other disputes begin. I see pan-Africanism as anything that joins in a struggle for the liberation and delivery from jeopardy of people of African descent at home or abroad. The philosophy governing it may vary from feminism, to Garveyism, to Marxism, and so on. The eminent African-American scholar W.E.B. Du Bois said these words: “I have made bold to repeat the testimony of Karl Marx, whom I regard as the greatest of modern philosphers.” Before I began to study more about the historic African philosophy coming out of Egypt, I also considered Marx the greatest of modern philosophers. Now I don’t know if there is such a person, but I would recommend even now, with all of the confusion going on, that the study of Marx—which is a dialectic drawn partly from classical Egyptian sources and partly from European sources—is essential for understanding the world as it evolved from the time of the Industrial Revolution and perhaps before. I don’t know if all of this is making sense, because I’m talking without a script.

WCA: You don’t need a script. The script is your life. I don’t think you need a script anymore. [chuckles]

EK: So, that is what we attempted to do in ASCRIA. The important thing about ASCRIA that most people do not know about is that ASCRIA was very focused on Guyana itself. We had to focus on Guyana itself, because Guyana emerged from a plantation colony with a multi-ethnic population. Each of them [Guyana’s ethnic groups] from a proud hinterland of experience in their particular origins from which they sprang: the indigenous people, who are still there; the Africans who were enslaved and transported (Van Sertima shed a lot of light on the many subtleties of the African experience); the Indians came from India, from a historic civilization where human beings did not shrink from aspirations of a non-material type. So ASCRIA confronted itself with a task of making sense of this post-colonial nonsense. ASCRIA tried to make sense of all of this and point Guyanese people toward a sense of nationhood, being a nation of diverse parts. We haven’t succeeded yet, but that does not mean it was in vain. There was a time when this was succeeding, but always there are forces who will not find it convenient and who will find other things more expedient or more to their advantage. Of course, they may be looking at us the same way, as being barriers to their sense of progress, you know? [chuckles]

The prime minister at the time of the pan-Africanist seminar was Mr. L.F.S. [Forbes] Burnham, who made himself Executive President ten years after that, soon after Walter Rodney had returned. I knew at the time that the sort of pro-independence and pro-liberation alliance that existed between ASCRIA and the People’s National Congress [PNC] was on shaky ground because there was no similarity of purpose, really. It came to a shambles in 1971 on the issue of what we in ASCRIA regarded as culture. In ASCRIA, we spoke of culture. Every Friday night in our headquarters at Third Street, Georgetown, we had a session called “ideology.” There, we hammered out, as best we could—you see, we had a night school in Georgetown teaching academic subjects to children who either could not afford high school, or their parents could not afford it for their children. They came there. At first it was free, and then we had some African mothers come in to teach and they said we should make this thing orderly by charging a small fee, so that we would know who really wants to come. So, they did that. They were free to manage it how they liked. So every Friday night we taught about “ideology.” In these ideological classes, we debated everything. People are writing today about ASCRIA and about myself or my colleagues, but know nothing about this.

We were the only organization in Guyana at the time that formally discussed certain issues. Our members were African, of course. We felt we had been charged with the responsibility of internal transformation before we can transform the world. So, we had to begin at home. In that beginning at home, we also tried to work out humane, humanistic, and reasonable relations between Guyanese of all origins. We debated, for example, the question, “Who is the enemy?” The popular feeling in Guyana among Africans at the time was that the enemy were Indians. Too many of them were rich, compared to Africans. The white man was declining; they were few in number—so it was the Indian you had to watch, they said. We worked on that inside ASCRIA. We taught that the origin of our oppression is European. We won that debate inside of the organization. Eventually, across other organizations and in academia, we became almost unanimous in saying that the enemy is Europe, not India. That, I consider a major contribution to the future. We did not hide it, but if anyone else knew about it, it has not been acknowledged.

The other important thing that I think we did was to interpret the experience of indigenous people. Among Africans, the most popular knowledge about Indigenous people in history, generally, was that Amerindians were the “slave-catchers.” Yes, they were slave-catchers, but they were not self-appointed! We described them as having been the military slaves of the plantation system, capturing Africans or whoever else was escaping from the plantation.

In these ways, we tried to humanize Guyana’s inter-ethnic relations. I don’t know what else we could do. We taught these things in our daily practice, all over the country, wherever we had compounds—African local organizations were called “compounds,” because this was the word we heard coming from Africa at that time—so we carried this kind of message throughout the country. It was not supported by any major media or anything like that. I mean, we were up against all sorts of institutions, beginning with the Church, you know? [chuckles]

WCA: Yeah, of course.

EK: The Church invited me once—not me only, but also seven other people who also taught and wrote—to speak about how we see the Church. I attended the session and I made a lot of emphasis on what the Church has done to African religion, having misrepresented it as magic, as so-called voodoo, simply because they did not understand it. These were traditions of deep spirituality, but because they [the Church] did not understand it, or did not want to understand it, they called it “evil.”

So, we were seeking to perpetuate authentic African culture among Africans in Guyana. My own family is an example. I got married in Guyana at the age of 46, after I met my wife in 1970 in California, where we were both living at the time. She was an African-American woman, now passed away, unfortunately. We were not married in a church. We were married in an African ceremony of the Yoruba tradition, by Yoruba people from the continent of Africa, who were in Guyana. One of them is still in touch with us. She is now a widow.

Our children were not baptized in any church. They got their names in an African naming ceremony on the eighth day after their birth, in presence of the public. Again, conducted by people from the continent of Africa. We were trying to demonstrate that there is a reality, a rectitude, a purpose other than the European, even previous to the European.

Now, in 1968 we launched the cultural revolution in Guyana. This excited some opposition among non-Africans. We had a little handbook, a few pages, called Teachings of the Cultural Revolution—it’s still available and if you speak to Nigel Westmass, he should be able to find a print for you. In this book, we tried to do something original. We had a Congolese man in Guyana at the time who gave us a version of Congol culture. We adopted it. Essentially, we were appealing to non-European races to stand on their own feet. We said that African people should choose

African names for themselves and for their children. We couldn’t do anything about the language, culture, or family practices that had been severed from us, but we could choose our names. We had books of African names compiled from various countries. We launched the cultural revolution one Sunday night after the Christian service at a nearby church had ended. We launched it to the flourish of drums! We had young people reading various pages of this small book. They read the whole book out loud that night. We got some back-pushing from the Church. They said we interrupted their services, which we did not. But in that book, we appealed to African-Guyanese not to be entrapped by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization culture. We appealed to Indian-Guyanese not to be entrapped by the Warsaw Pact culture. So, although we are African and don’t apologize for that, we were not separatists in the sense that we came to recognize—or our focus was making a life that all could enjoy, one in which we could all be comfortable and respected.

So, that is something I wanted to mention with regard to your question. Let me stop there because I am old and long-winded.

WCA: You’ve brought up a lot of points that lead into my next question. I wanted to also ask you about the Working People’s Alliance (WPA) and its evolution into a party. What do you think about the WPA now? As it became a party, was the intention of the WPA to get people elected to Parliament, and to eventually govern or control the state? Can you reflect on some of those things, like the goals of the WPA and how it eventually became a political party?

EK: I want to mention, as you know, that we [the WPA] began as a coalition of independent groups who were alarmed at the rise of dictatorial tendencies in the state at that time, beginning early in the 1970s and going on into the period you’re discussing. We had not thought of ourselves as that kind of political party. We wanted to improve the politics of the working people. That was clearly stated. We had no intention of parliament or anything like that, but events overtook us. We had to either

struggle or surrender.

Walter Rodney returned in 1974 and began to look around. He was someone I had barely known. He used to come home on holiday from Tanzania. Of course, when he was banned from Jamaica, ASCRIA had protested. It was known that we had a different kind of foreign policy and international compared to the PNC, although the racial violence of the 1960s had put us on the same side of the PNC in the interest of security. We did not get involved with them and their international dealings. In fact, one of our points of breaking with them was when I was General Secretary of the PNC, the aspiring Prime Minister [Forbes Burnham] wanted to send me to the United States of America, to a church, to receive money—a donation. I said, “Sir, I don’t know the country. I’ve never been there. Who are these people?” [Laughter]

Well, he was very angry. He said, “This is the third time in my political career that you are acting as an obstacle to me.” The first time was within the PPP, when he wanted, after just returning from England, to usurp the position of leadership from [Cheddi] Jagan. And I, as a village boy, told him, “This is absurd.” This man was vain. In the 1940s, I had worked alongside talking to people in the villages. I had supported him in 1946, when we formed the Political Affairs Committee, to the time he entered parliament in 1947, when I supported him also. And now, suddenly, this gentleman, quite a promising young African, comes back from studies in England and instantly becomes the leader of the party? I don’t know about that. So, I opposed him. So that’s twice. According to him, there was a third time.

After the elections in 1953 when the PPP had been founded, we kept the chairmanship open for Mr. Burnham. He had been a Guyana scholar. Brilliant. Very famous, and all of that—but did not have a record of struggle in Guyana. But we thought he was the person whom people would most appreciate among the up-and-coming and upper-middle classes of African and Indian Guyanese. They respect education, you know? They respected his education; they respected his brilliance; they respected that he was a Guyana scholar; they respected that he was a man who had left and come back, and all of that. So we thought the chairmanship was automatically Burnham’s position and nobody contested it.

Just before the elections, there was a congress held in Georgetown starting about 5pm one evening—so that the majority of the people attending the congress would be city people. The country people had gone, they had to get home. Some had to get to Berbice. There comes up a motion from the floor. Whereas there was only one PPP member in the parliament at the time, namely Dr. Jagan, we should not elect the leader of the legislative group (this was a term we copied from the PNP in Jamaica). We should wait until the elections are over and then hold our election for that position. So, I smelt a fish. And so, all I did was to get up and say, “Yes, but that would mean a vote of no confidence in the present holder of the office,” who was Jagan. I didn’t say, but it was also implied, that we would be going into the election without a party leader. The motion collapsed under its own weight.

So, that must be the other time that Burnham was talking about when I got in his way, but it was nothing against Burnham at all. I was just dealing with the organic political development. Nothing about him.

So, Walter Rodney returned in 1974. He used to come to the ASCRIA Hall when he visited on holiday maybe twice during his Tanzania years. He would come to the building and talk with me. He was a different generation—a younger generation than mine. He couldn’t have been my schoolmate or anything. I didn’t go to Queen’s College. I never went to high school. I’m a purely primary school person. But, he used to come to ASCRIA to spend a few minutes and talk. He also went to Freedom House, because he respected Dr. Jagan’s pioneering work—and probably for other reasons that were no business of mine—but, he would tell me that he was going to see Jagan afterwards. So, when he came back to stay, and news broke that he had been appointed by the academic board to head the history department, the University Council—which is a political body making political choices—overturned his appointment. Just like that. So, it was ASCRIA that took up that fight.

We took up the fight in this way: we invited all political organizations of the opposition, including the PPP, to join a movement to resist and to demand the appointment of Walter Rodney. Up to that time, it was impossible for Dr. Jagan to speak in Georgetown. He had no audience in Georgetown. We would heckle him to death. Knowing what Walter Rodney had written about indentureship and slavery, we argued in ASCRIA that we could not make his issue an African issue. It was a national issue. He had put himself on record. We therefore invited all political organizations, and they all accepted and came. They were furious. The meeting exploded out onto the streets. People were standing shoulder-to-shoulder on the streets resisting this thing. Everybody wanted Walter Rodney teaching history.

The first meeting we held was broken up by PNC thugs. A policeman came next to me and said, “Mr. Kwayana, this thing is not going to stop until black dog eat black dog.” Do you understand?

WCA: Yeah.

EK: That was his language. He was thinking of the role of policemen in this situation. They were there to break up this meeting, and it broke up, because we read a passage from The Groundings with My Brothers, in which he talked about slavery and indenture, and forming a companionship among the descendants of the two groups. In that atmosphere, things developed from one stage to the other. This group, which had intended to be a coalition working together in small groups, improving the politics of the working people, putting trade unions back in control, rather than being controlled by a political party (as was happening at the time)—all of that became secondary.

The first paper we printed, Day Clean, could not be printed in Guyana. Nobody would print it because Burnham had already introduced newsprint control. He said, “If you print this paper, we won’t let you print.” He knew the mind of the reader. So we printed it in Trinidad. When it arrived, before it could be rounded up and taken in, Burnham passed a special order in through his cabinet banning it. They didn’t ban it as if they were banning literature. They banned it as if they were banning swordfish! They banned it under one of those executive orders used to ban fish or anything else like that. But some copies leaked out and got into the hands of the people.

From then on, the battle was joint. What was supposed to be a coalition of forces focused on the politics of the working people was now a struggle for democracy. You can investigate the rest, there was a lot of documentation of all this. We had to spearhead the struggle for democracy.

The PPP wanted power, yes. But the PPP also had a view of the world that did not urge them to struggle in the same way as we were struggling, for an authentic system developed by the working people, managed by the working people, men and women.

If you read the PPP literature, they were waiting for the Soviet Union to win the international struggle. They didn’t say it in those words, but they were getting a lot of financial support. They had an import and export agency that carried out heavy trade with Eastern Europe. So, comradeship, going into trade—profits and everything—and what they did with the money nobody knows. And that was only one instance. So, they could take their time. They could play the parliamentary game. They thought they were going to win the world struggle first and then they would come into their own. This is how I read them. In fact, one of their members did say, at a trade union meeting in the 1970s, I think. He said, “We are winning the world struggle.” So that puts people in a different kind of temper, you know? You lose agency. You lose your sense of responsibility because your partners are going to win the world struggle and then promote you.

That creates a lot of complexities, you know? Like in 1977, when Rodney was writing “Government of National Unity and Reconstruction,” the PPP was writing “National Patriotic Front.” It was an arrangement similar to what they had in Eastern Europe, where the Communist Party had liberated people from the Nazis, appointed governments of the Communist Party, or other parties that accepted, in their words, “the leadership of the working class.” That means, you let the Communists carry on and you are there as part of a front with no pull whatsoever. I saw that in their teaching. Anyway, I hope that partly answers your question.

So, the thing that pitched us into that was the burning of the Office of the General Secretary and the Ministry of National Development building [during a protest in 1979]. In 1974 the PNC had created something called the Office of the General Secretary and the Ministry of National Development, which was a political party and ministry rolled into one. Don’t ask where the money is coming from—it’s coming from the treasury! [Laughs.]

Dr. Reid was the person in that office. Poor Dr. Reid learned politics in his old age and was, you know, very new to everything. He was discovering a new world. … So, when Dr. Walter Rodney, Dr. Omowale, and Dr. Rupert Roopnaraine were arrested after the burning of that building, the response of the people was magnetic. They poured out onto the street to resist. That is when it was decided to form the Working People’s Alliance as a political party. Things were done very rapidly.

WCA: So, at the beginning of the interview, you said that there is a need for new ideas and new thinking. I read your book, The Bauxite Strike and the Old Politics. In that book, you say a lot of things, which would probably be considered more controversial to more orthodox Marxist thinkers, about the self-activity of workers and things happening autonomously amongst people. I was wondering if you could offer any new thinking around self-activity and self-organization, as opposed to the traditional but failed approaches of trying to work within state power.

EK: I have been out of Guyana since 2002. And I have never stayed abroad and told people what to do. It’s no different now. I have ideas of what I think should be done. I do not know what this group, that group, or the other group, may be doing. I do not have the kind of ego for telling people what to do when they are on the spot. I try to offer my support and solidarity whenever I see something good; or carry an independent line of my own, which disturbs the source of all this oppression and repression. But please, do not expect from me an answer about what I think should be done. I don’t know, frankly. And I’m not ashamed that I do not know.

I don’t know enough to pronounce on the situation. Where I feel that I can pronounce, especially with respect to legal instruments and constitutional provisions [in Guyana], I write and I stand by what I write. But staying at this distance after this long absence and pretending that I can advise people—no. [Laughs.] I can talk with people; I can bring another point of view, but I’m not there.

I wish people unity and solidarity in their struggle against oppression. I wish them safety and salvation. I wish them the right path of action that will help them in their self-emancipation. I stand with Walter Rodney and say that self-emancipation is the only true emancipation. If somebody else emancipates you, you’re not emancipated! It has to be self-emancipation. If we examine the great movements of history, they have all been for self-emancipation.

I can assure you that my thoughts are there [in Guyana] all the time and what I’m saying here is not callousness. It’s not lack of concern. I am over concerned! You may know that my vision has gone. I can’t read anymore. I have been writing through dictating, with the help of some very self-sacrificing people. The main one of them passed away. So I’m left in a kind of space with only odd helpers now and then. So, that is all I can do at this time.

So, I have no solution. My solution is: find a way in the struggle.

WCA: Honestly, that answer makes me respect you more, even if it’s a non-answer. I appreciate people who don’t feel that they can dictate the one-size-fits-all approach to revolution. I only have one question left for you. What do you want your legacy to be?

EK: Oh, forget it! I’m not going into that. [Laughs] I want people to see me as a person who tried to be fair. That’s all I’m concerned about. [Laughs] I don’t really think in those terms. I’m an ordinary village boy. If anybody sees me with a legacy they may think I stole it! [Both laugh]

WCA: So, is there anything that you would do differently?

EK: You have to give me time to think about that, let me see… I wouldn’t be surprised if there was. Ask me again sometime later. I can’t think of anything specific now, but hopefully, I can find something.

WCA: Brother Eusi Kwayana, thank you so much for taking the time. If you don’t mind, I’ll give you a call back to continue our conversation if that’s okay.

EK: Yes, and please call again if you don’t hear from me. I’m available. Thank you for that. […] Good luck with your pursuit. I hope that it is something that will benefit humanity.

WCA: I hope so, too. Thank you for saying that, Brother Eusi. I appreciate you talking with me.