In the U.S., when Black people suffer and die, it’s considered progress. How we produce and digest historical narratives has everything to do with it. Selective remembrances are the tools politicians, institutions, and the state use to shape how people feel about themselves. This happens to such an extent that it’s been possible to convince far too many people that they’re supposed to die for the U.S. nation. This logic isn’t exclusive to the U.S., because nationalisms employ this strategy around the world. However, the narrative of selective sacrifice deployed against Black Americans is a barrier imposed on the struggles for liberation, and must be directly challenged.

One of the best places to examine the manipulation of history for the sake of nationalism is U.S. elections. A regular line you hear directed at or from Black people is about how all of our ancestors died so that we could attain the right to vote. This simply isn’t true, not because it didn’t actually occur at times, but because it homogenizes Black politics. Patriotism is centered by overemphasizing one aspect of Black history and erasing other dissident aspects. While some Black people did believe the right to vote was important, others did not and there’s a record of their opposition.

One person who embodies the complexities and complications of this history is Lucy Parsons. The Black anarchist revolutionary was born into slavery, but she left a clear documentation on how she felt about voting. In one of her clearest condemnations of voting, Parsons wrote, “The fact is money and not votes is what rules the people. And the capitalists no longer care to buy the voters, they simply buy the ‘servants’ after they have been elected to ‘serve.’ The idea that the poor man’s vote amounts to anything is the veriest delusion. The ballot is only the paper veil that hides the tricks.” Parsons was decrying the demoralization of voting for representatives that are beholden to corporate power and hoping for incremental change on a cyclical basis.

And it shouldn’t be ignored that when she wrote this in 1905—she was arguing against voting decades before Black women would even have the right. Similarly, Black men who shakily had the right to vote rejected it too.

In 1956, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote an infamous piece for The Nation titled I Won’t Vote. One of the most well known representations of Black history, Du Bois was many things throughout his life, including someone who vehemently opposed the rationale of voting for the “lesser evil.” Du Bois clearly stated his position writing, “In 1956, I shall not go to the polls. I have not registered. I believe that democracy has so far disappeared in the United States that no ‘two evils’ exist. There is but one evil party with two names, and it will be elected despite all I can do or say.” He lamented more stating, “Stop yelling about a democracy we do not have. Democracy is dead in the United States. Yet there is still nothing to replace real democracy.” Despite being a towering figure in the imaginations of many liberals, Du Bois’ position on voting often falls by the wayside. Though he and Parsons represented very different sets of radical politics, they shared similar condemnations of the electoral process as a meaningful practice for securing needed change. Their differences only strengthen their shared critical analysis.

These examples and more show why it’s contemptible that those whose inheritance is racial power gained through the destruction of Black people, now instruct Black people to vote because “our ancestors” died for it. In keeping with the tradition I’ve highlighted, when civil rights leader and statesman John Lewis passed away in 2020 many politicians used his passing to galvanize voters. Though it’s no secret that Lewis was certainly an advocate of voting, he famously said, “The right to vote is the most powerful nonviolent tool we have in a democracy. I risked my life defending that right. Some died in the struggle.” Lewis’ fellow members of the Democratic Party establishment have perfected using the vote as a way of chastising Black people at the expense of Black revolutionary history. At his funeral, former President Bill Clinton used his eulogy to disparage Kwame Ture (formerly known as Stokely Carmicheal).

Clinton used this time at the podium to recall how, “There were two or three years there, where the movement went a little bit too far towards Stokely,” before declaring that “in the end, John Lewis prevailed.” This deplorable offense highlights the issue at hand. The former head of state weaponizes a historical difference, to reinforce the prevailing assumption.

Moreover, Clinton’s denigration of of Ture was a calculated response to critique. In an interview following the 1992 election, Ture addressed his feelings about voting and Clinton who he dismissed for not “understanding anything at all about history.” “The American capitalist system, as a backwards system, has a way of presenting history as if history is made by one man, one great man, one great woman,” said Ture. He analyzed how the Revolutionary War is condensed into George Washington, or how the Civil War is reduced to just Abraham Lincoln, or how the Civil Rights bill becomes narrated as Lyndon B. Johnson’s achievement, to which Black people must be grateful. Ture remembered how “while [Johnson] was signing, we were in the streets burning the country down. You better hurry up and sign it!”

Ture explained how it was only “the masses of our people properly organized in a determined, uncompromising, relentless struggle against the enemy” who could be depended upon. Of himself, he said “I’m not a Democrat. I’ve never voted in my life for the Democratic Party and I’ll never vote in the Democratic Party, it’s racist and it’s capitalist to the core. This is understood. And I shed my blood for the vote now, I want to make that clear. Some people get confused, the vote for me has never been the road to liberation.” Further, he added voting made people “politically irresponsible” and called it the “height of bourgeoisie propaganda” to think that voting once every four years could constitute political responsibility when politics is a constant part of everyday life. This criticism is part of the lineage of a Black critique on voting that obliterates the myth that “our ancestors” all died for the vote rather than for resources they hoped to attain by voting or not voting, and organizing outside state politics.

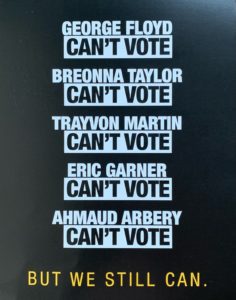

Though both part of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and the larger Civil Rights movement, Kwame Ture and John Lewis represent distinct parts of it. They diverge no different than people always have because movements are made up of complex people and differences. This is inconvenienced by neat narratives presented to us in partisan history books, encyclopedic museums, and in liberal efforts such as the 1619 Project which falsely states that, “America wasn’t a democracy until Black Americans made it one.” The present reveals as Du Bois pointed out many decades ago—this country is not a democracy. During the 2020 election, visuals of Black people risking their lives to vote in a pandemic were turned into patriotic drivel. One prominent Black journalist went as far as to tweet a photo of a young Black mother and her small child encased in a plastic bubble in an early voting line writing, “Don’t ever say we don’t love America.” “We” don’t, some do, but not we.

Distorted versions of history insist messianic leaders were required in the struggle, and fails to render Black people as capable of determining things for themselves. The state perpetuates an idea that we need a charismatic shepherd, be it a celebrity, politician, the wealthy Black elite, or otherwise to negotiate the terms of our lives. This happens so much so that based on visibility alone, these types of figures become spokespeople for Black America. It doesn’t have to be because of good work, knowledge, or solidarity with those in the mud of capitalistic onslaught. Progress misdefined is a barrier to our liberation.

Liberalism needs its myths. Patriotism and integration mythology make Black deaths into a necessary sacrifice to get Black people to where we are today. This same today of purged voter rolls, closed polling places, stolen elections, and rigged processes eroding the illusion of “rights.” This same today where the lesser evilism Du Bois decried remains disturbingly relevant. Yet, it’s overlooking these parts of history that entraps us in cycles that should have long been abolished. If we knew more about the people who rejected voting and divested from the project of the U.S. nation state, maybe we would be experiencing a different reality. Instead, we’re stuck in one where there’s an overabundance of falsity working to convince us that we should toil to enable the machinery of a racistly repetitive system because our ancestors all supposedly did.

Experiencing abuse and oppression does not equal love. Black suffering gets fetishized and struggles for liberation are framed as being for the betterment of the state. Black history gets twisted, co-opted, and misrepresented so frequently that people believe masses of us dying, and suffering, are necessary to help the state develop a conscience it will never have. Hard learned lessons get lost in favor of stories about patriotic duty, for the advancement of a country instead of for our survival. The liberal idea of democracy and progress leans on Black longsuffering, which is why it periodically doles out disingenuous “thank yous” to Black people who “save America” from itself at our own expense.

Black people have rebelled, risen up, and even killed, seeking liberation in a number of ways. Flattening complex histories to fit comfortable state-preferred narratives is a loss that doesn’t bear repeating. No, all the ancestors didn’t die for the vote, for integration, or for the U.S. And those who did not shouldn’t be erased. Well over a century ago, Lucy Parsons wrote we must be reminded that “the sword still hangs upon the wall” and it “will be unsheathed again, if necessary, in defense of your rights.” In order to do so, we have to be able to recall that there was a sword in the first place. We are tasked with asking questions and remembering everything; and not just remembering what’s convenient for the preservation of structures that are still killing us in the present day. We can keep trying to “save” the nation, but the nation will never save us

William C. Anderson is a writer whose work has been published by The Guardian, Truthout, MTV and Pitchfork, among others. He’s co-author of As Black as Resistance (AK Press 2018) and author of the forthcoming book The Nation On No Map (AK Press 2021).